In the centre of the South Pacific, there's a place as far away from land as anyone on Earth could ever hope to get. The ocean is different there.

These distant waters lie at the heart of the South Pacific Gyre, the centre of which holds the 'oceanic pole of inaccessibility': the ocean's remotest extreme, aka Point Nemo (a name meaning 'no-one'), famous otherwise for being a spacecraft cemetery.

But aside from the ghosts of burnt-up satellites, what dwells under these far-off waves?

Not much, scientists have long thought. Despite taking up 10 percent of the ocean's surface, the South Pacific Gyre (SPG) – the largest of Earth's five giant ocean-spanning current systems – is generally considered a 'desert' in terms of marine biology.

Nonetheless, stuff does live there, even if organic life in these waters (and the seabed below it) is few and far between, due to a range of factors.

These include distance from land (and the nutrient matter it provides), the way water swirling currents isolate the centre of the gyre from the rest of the ocean, and high UV levels in this part of the ocean.

In truth, though, we don't actually know all that much about the life-forms that inhabit the SPG, largely because of how hard it is to study this oceanic desert – due to both its extreme remoteness, and also how large it is, covering about 37 million square kilometres (14 million square miles).

Despite the challenges, a recent international research effort has given us what the scientists claim is an unparalleled glimpse at the microbial creatures that exist in these waters.

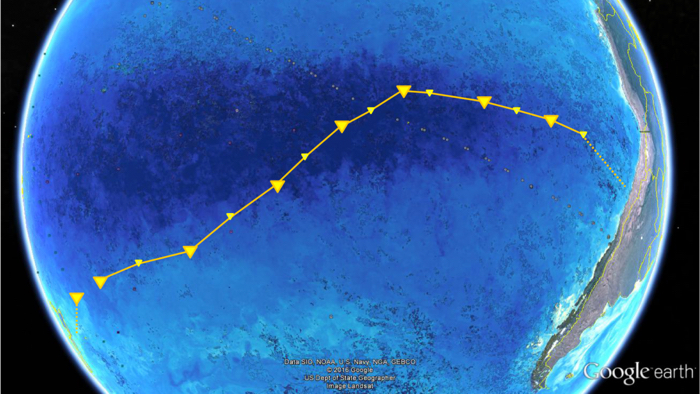

During a six-week expedition aboard the German research vessel FS Sonne from December 2015 to January 2016, a crew led by the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology sailed a 7,000-kilometre (4,350 miles) journey through the SPG from Chile to New Zealand.

En route, they sampled the microbial populations of the remote waters at depths between 20 to 5,000 metres (65 ft to 16,400 ft), using a newly developed analysis system that enabled the researchers to sequence and identify organic samples en route in as little as 35 hours.

(Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology/Google Earth/NASA)

(Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology/Google Earth/NASA)

Above: FS Sonne's path crossing the SPG from Chile to New Zealand.

"To our surprise, we found about a third less cells in South Pacific surface waters compared to ocean gyres in the Atlantic", said one of the researchers, microbial ecologist Bernhard Fuchs, back in July 2019.

"It was probably the lowest cell numbers ever measured in oceanic surface waters."

Among the microbes the team found, 20 major bacterial clades dominated the lot. These were mostly organisms scientists have encountered in other gyre systems, such as SAR11, SAR116, SAR86, Prochlorococcus, and more.

One of the populations identified, called AEGEAN–169, was particularly numerous in the surface waters of the SPG, whereas previous research had only discovered them at 500-metre depths.

"This indicates an interesting potential adaptation to ultraoligotrophic [low in biological productivity] waters and high solar irradiance", said one of the team, microbiologist Greta Reintjes.

"It is definitely something we will investigate further."

On the whole though, the sampling generally confirmed that the SPG is a "unique, ultraoligotrophic habitat", where low nutrient availability restricts growth to specialist oligotrophic organisms and creatures that have adapted to "extreme physicochemical conditions".

In other words, the SPG can't shake off its 'desert' reputation just yet, but there is a bright side to all that organic absence: these distant, almost lifeless waters are said to be the clearest ocean in all the world.

The findings were reported in Environmental Microbiology.

A version of this article was first published in July 2019.

Source: https://www.sciencealert.com

These Android screens look like the perfect upgrade for any car. The interface appears responsive and easy to use, ideal for modern driving. Very well-designed products. android car stereo systems

ReplyDelete